If you’ve ever sung ‘London’s Burning’, ‘Frère Jacques’, ‘Campfire’s Burning’ then you’ve sung a round or catch! But how are such simple songs – which we associate primarily with childhood – a subject for research?

Rounds and catches are an easy way of singing in harmony. Everyone sings the same melody, but starting at different times, creating instant harmony! The chances are you’ll have sung a song like this – London’s Burning, for example – but probably not since childhood. This is one called ‘Up and Down the World Goes’ (we sing the melody first and then split into the round):

Unless you’re in a choir, the chances are you don’t sing very often with other people. However, in early modern Britain singing together was popular entertainment for all ages, genders and classes.

Without televisions, social media and the internet, singing was how you had fun and connected with friends and family. Our modern idea of being ‘musical’ or not didn’t really exist. To be human was to be musical (devils, demons and monsters were unmusical!)

Typically, though, we’ve imagined this popular, communal singing to have been everyone singing one tune together. Singing songs in harmony – sung as madrigals or motets or partsongs – required musical literary and therefore the preserve of the elite – whether professional musicians or highly educated amateurs.

Ballad-singing was indeed very popular and cheaply printed sheets were frequently published in large numbers to provide new, topical lyrics to be sung to well-known tunes. However, rounds and catches which could be learnt aurally and picked up through joining in, were an accessible form of singing in harmony which people across the social spectrum took part in.

Music that primarily circulated orally can be hard to study as often little record survives. However, because the singing of rounds and catches was enjoyed across society, in some contexts these songs were written down and a few collections survive.

The earliest major collection of these songs was copied by an ex-chorister called Thomas Lant who was a servant in the household of the Cheyney family in Bedfordshire (who are known to have had musical interests). In 1580 he began copying catches that he came across into a compact roll of parchment (digitised by King’s College, Cambridge) – small enough to fit in a pocket and be taken down the alehouse or brought out after dinner to lead singing with the Cheyney family perhaps?

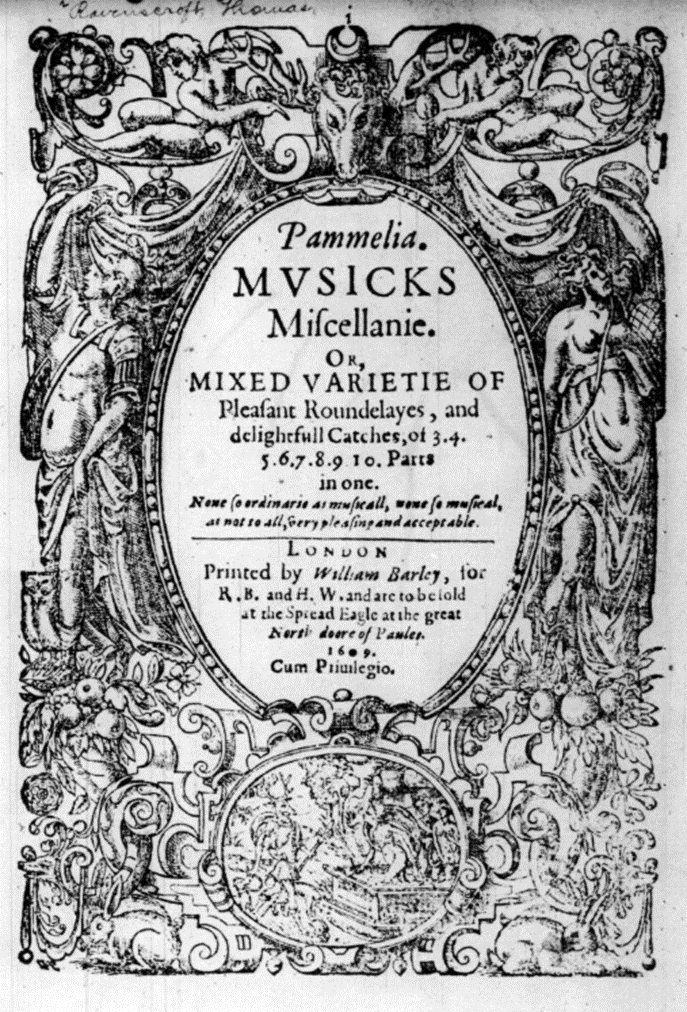

In the early seventeenth century, an other ex-chorister, Thomas Ravenscroft, published a collection of rounds and catches called Pammelia (1609). Despite the 30-year time gap, Lant and Ravenscroft share many of the same songs, implying that there was longstanding corpus of widely known catches in circulation..

Lant and Ravenscroft’s collections recorded a wide variety of songs from all sorts of contexts. Some are short and simple, others are longer, wider in range and harder to sing. While most are in 3-4 parts, some are in as many as 11. Most are in English, but there are some in French and Latin. There are songs about drinking, singing, friendship, love, street cries, shepherds, hunting, bells, religious faith, ships, soldiers, tongue-twisters… All sorts of aspects of Tudor life!

To help us understand the contexts in which these songs were sung, we can turn to early modern literature. Plays, jestbooks (which narrate the comic exploits of loveable rogues) and other literature depict scenes in which catch-singing takes place. A famous example comes from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, in which Sir Toby and Sir Andrew disturb the peace of Olivia’s household with their night-time catches and are rebuked by the steward Malvolio for turning her house into an alehouse.

Studying rounds and catches enables us to explore the role of song in the everyday lives of early modern people. Who sang catches together and in what contexts? What social functions did catches serve? How did catches define communities? Did everyone approve of catch-singing? Or could catch-singing also be a source of conflict or disruption (as in Twelfth Night).

I also wonder what we might learn from catches today? What benefits have we lost from the decline in singing together? What might be again by reviving and adapting catch-singing practices in our communities?

Through both historical research and practical singing with modern singers of varying ages and abilities I hope to answer some of these questions over the next year!.